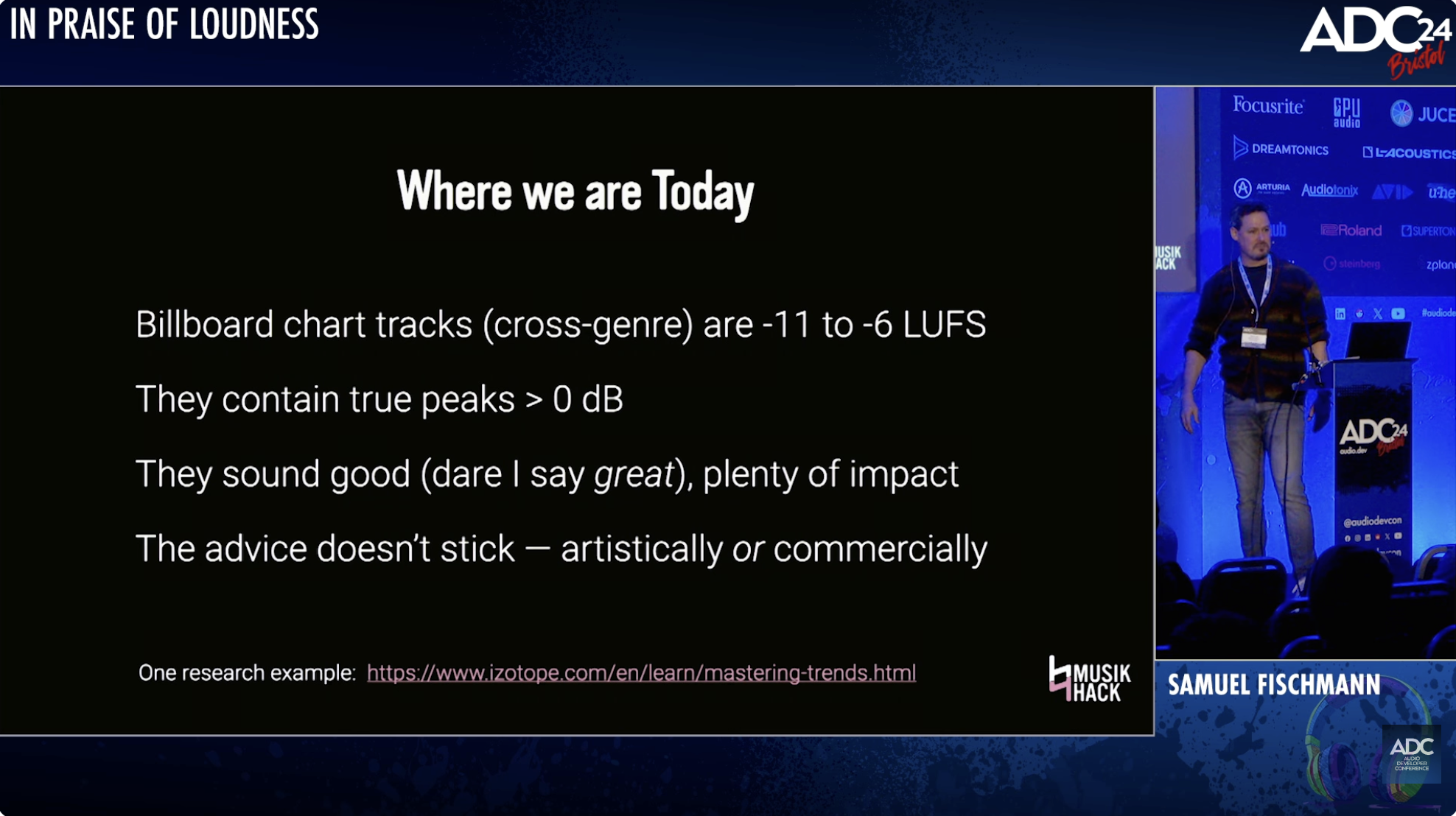

The pros don’t care about -14 LUFS/-16 LUFS all, and as an indie producer, mixer, or mastering engineer, neither should you. Simply looking at a Billboard chart will show you that most music with high production values is still being mastered around -8 LUFS. For a deep dive on everything about LUFS and loudness, check out this talk I did at ADC 2024 in Bristol, "In Praise of Loudness!" For an overview in words, jump below...

Here’s how these numbers became ubiquitous:

Broadcasters (TV for example) and streaming media providers (like Spotify) were getting inconsistent volume as their number one customer complaint. As a result, standards bodies in Europe (EBU) and the US (AES) worked hard to develop guidelines to solve the issue via track metadata and volume normalization, then published them.

At first it seems simple: pick a loudness target. Push loud tracks down and quiet tracks up. But then, when you push quiet tracks up, you push any peaks in that material above 0 and need to slap on a limiter. When thinking about raising up a quiet track, the standards bodies came to realize this was a big problem for music that’s relatively quiet, but still has some loud peaks. Can you imagine how bad classical music — with a really low integrated LUFS value — would sound, normalized up and smashed into a limiter? And what about non-music material, such as film audio or podcasts? In the end, EBU decided everybody should broadcast at -23 LUFS. That gave them the ability to reduce loud material way down to match high dynamic range material like classical or non-musical broadcasts, and they wouldn’t need to push very many things up.

As it turns out, portable music players don’t have the juice to play music loud enough for consumers when material is delivered at that level, and they have too much noise in their amplifiers, which would make the signal to noise ratio bad if you cranked it. So the standards bodies said fine, we’ll make more standards to try and get manufacturers to make higher quality portable amps (good luck with that!) and said we’ll relent for music and suggest -16 LUFS instead. The AES calls out the aspirational target of -23 LUFS, but never bothered to recommend it in today’s environment.

But wait! Albums intentionally have tracks at different volumes, so how do we maintain that while normalizing? The standards bodies decided OK, we’ll take the loudest track (by LUFS) on the album and normalize it to -14 LUFS, so that it’s a little louder than our target, and use the same normalization factor on all the rest of the tracks to keep them relatively matched for album listeners. We’ve now arrived at -14 LUFS: a double compromise based on the difficulty reconciling the dynamic range of different audio content. Not only that, we’ve learned the risk of distorting your track on delivery comes from providing a track that’s too quiet, not too loud! That’s when a client might use a limiter.

None of this originally had to do with audio quality during mastering or delivery, however. It was all about how broadcasters maintain existing quality while normalizing. If you ever see anybody telling you your music’s quality will be better if you stick to -14, or -16 LUFS, that’s the origin of those numbers; look for better advice! You may also see people say that high LUFS cause intersample/true peaks due to lossy codecs and your DAC, but that’s incorrect. A true peak meter will tell you whether or not you have that problem. If that meter is not showing a problem, a LUFS meter won’t suddenly provide a better true peak picture.

The arguments that high dynamic range material always sounds better are secondary at best. It depends on the material, and there’s not really a good way to compare in general, since many techniques can decrease your dynamic range and they all sound different. That’s why we pay mastering engineers! Additionally, one of the advantages of high LUFS is that your music will be easier to hear consistently in loud or background environments without applying compression on-device. Honestly, that is the majority of listening situations for pop music: car, bar, on a run, in a cafe, on public transport without expensive noise cancelling headphones. It’s also the reason the low LUFS and wide dynamic range of classical recordings makes them awful to experience in those environments. This doesn’t mean they are badly produced, just that their range requires quiet, predictable environments in order to enjoy them. Evangelizing high dynamic range at the cost of loudness for all music is just as bad as evangelizing loudness at the cost of high dynamic range for all music. We must consider the style of the music and the environment in which it’s listened to! That's why mastering to your ear is so important, and one of the main reasons we made Master Plan.

Anyway, what happened after these standards were published is that streaming services issued guidelines to artists based on them, then a bunch of internet gurus had hot takes on the guidelines. The result is a lot of confused advice aimed at the wrong audience. It was always supposed to be the broadcaster’s job to adhere to loudness consistency. Not yours. The guidelines issued don’t often make sense, either! Spotify says to deliver at -14 LUFS, then lets premium users turn on loud normalization, which would ignore your headroom and push your track 3dB through a limiter you do not control to get to -11 LUFS. If you want your music to be streamed as you mastered it, your masters would have to be at least -11 LUFS.

Paradoxically, the louder LUFS your mix is, the less likely a streamer will distort it, because the danger comes if the streaming client decides to normalize upwards. That varies by client and I’ll bet my favorite synth they will keep changing their behavior over time. Under the current system, your track will always be safer if it’s louder than that target. So, the pros just keep making music the way they always have, the way it sounds good to them: these targets are the broadcaster’s responsibility, not theirs, and not yours. Remember: your ears matter more than your meters!